Fossil finger points to new human species

DNA analysis reveals lost relative from 40,000 years ago.

Rex Dalton

In the summer of 2008, Russian researchers dug up a sliver of human finger bone from an isolated Siberian cave. The team stored it away for later testing, assuming that the nondescript fragment came from one of the Neanderthals who left a welter of tools in the cave between 30,000 and 48,000 years ago. Nothing about the bone shard seemed extraordinary.

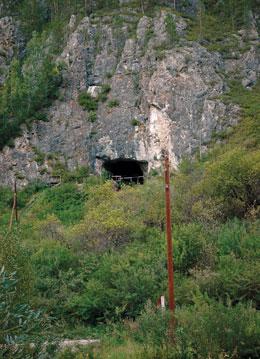

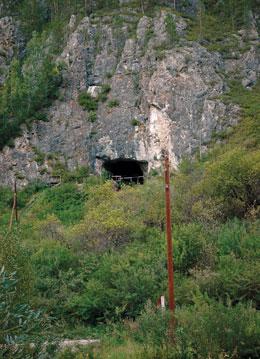

A finger bone found in Denisova Cave in Siberia could add a branch to the human family tree.B. VIOLA

A finger bone found in Denisova Cave in Siberia could add a branch to the human family tree.B. VIOLAIts genetic material told another story. When German researchers extracted and sequenced DNA from the fossil, they found that it did not match that of Neanderthals — or of modern humans, which were also living nearby at the time. The genetic data, published online in Nature1, reveal that the bone may belong to a previously unrecognized, extinct human species that migrated out of Africa long before our known relatives.

"This really surpassed our hopes," says Svante Pääbo, senior author on the international study and director of evolutionary genetics at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany. "I almost could not believe it. It sounded too fantastic to be true."

Researchers not involved in the work applauded the findings but cautioned against drawing too many conclusions from a single study. "With the data in hand, you cannot claim the discovery of a new species," says Eske Willerslev, an evolutionary biologist and director of the Centre for GeoGenetics at the University of Copenhagen.

“I almost could not believe it. It sounded too fantastic to be true.”

If further work does support the initial conclusions, the discovery would mark the first time that an extinct human relative had been identified by DNA analysis. It would also suggest that ice-age humans were more diverse than had been thought. Since the late nineteenth century, researchers have known that two species of Homo — Neanderthals and modern humans — coexisted during the later part of the last ice age. In 2003, a third species, Homo floresiensis, was discovered on the island of Flores in Indonesia, but there has been no sign of this tiny 'hobbit' elsewhere. The relative identified in Siberia, however, raises the possibility that several Homo species ranged across Europe and Asia, overlapping with the direct ancestors of modern people.

The Siberian site in the Altai Mountains, called Denisova Cave, was already known as a rich source of Mousterian and Levallois artefacts, two styles of tool attributed to Neanderthals. For more than a decade, Russian scientists from the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnology in Novosibirsk have been searching for the toolmakers' bones. They discovered several bone specimens, handling each potentially important new find with gloves to prevent contamination with modern human DNA. The bones' own DNA could then be extracted and analysed.

When the finger bone was discovered, "we didn't pay special attention to it", says archaeologist Michael Shunkov of the Novosibirsk institute. But Pääbo had established a relationship with the Russian team years before to gather material for genetic testing from ice-age humans. After obtaining the bone, the German team extracted the bone's genetic material and sequenced its mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) — the most abundant kind of DNA and the best bet for getting an undegraded sequence from ancient tissue.

After re-reading the mtDNA sequences an average of 156 times each to ensure accuracy, the researchers compared them with the mtDNA genomes of 54 modern humans, a 30,000-year-old modern human found in Russia and six Neanderthals. The Denisova Cave DNA fell into a class of its own. Although a Neanderthal mtDNA genome differs from that of Homo sapiens at 202 nucleotide positions on average, the Denisova Cave sample differed at an average of 385 positions.

The differences imply that the Siberian ancestor branched off from the human family tree a million years ago, well before the split between modern humans and Neanderthals. If so, the proposed species must have left Africa in a previously unknown migration, between that of Homo erectus 1.9 million years ago and that of the Neanderthal ancestor Homo heidelbergensis, 300,000 to 500,000 years ago.

Study author Johannes Krause, also at the Max Planck Institute in Leipzig, says that the researchers are now generating nuclear DNA sequences from the bone with the hope of sequencing its entire genome. If they are successful, it would be the oldest human genome sequenced, eclipsing that of the 4,000-year-old Eskimo from Greenland that Willerslev and his colleagues reported last month2.

A complete genome might also enable the researchers to give the proposed new species a formal name. They had originally planned to do so on the basis of the mtDNA genome. But they opted to wait until more bones are found — or until the DNA gives a clearer picture of its relationship to modern humans and Neanderthals.

Willerslev emphasizes that, on its own, the mtDNA evidence does not verify that the Siberian find represents a new species because mtDNA is inherited only from the mother. It is possible that some modern humans or Neanderthals living in Siberia 40,000 years ago had unusual mtDNA, which may have come from earlier interbreeding among H. erectus, Neanderthals, archaic modern humans or another, unknown species of Homo. Only probes of the nuclear DNA will properly define the position of the Siberian relative in the human family tree.

Anthropologists also want to see more-refined dating of the sediments and a better description of the finger bone itself. "I haven't seen a picture of the bone, and would like to," says Owen Lovejoy, an anthropologist at Kent State University in Ohio. "The stratigraphic age for the bone is 30,000 to 48,000 years old, but the mtDNA age could be as old as H. erectus," says Lovejoy. "That doesn't tell us much about human evolution unless it truly represents a surviving ancient species."

The cave has yielded few clues about the culture of the Siberian hominin, although a fragment of a polished bracelet with a drilled hole was found earlier in the same layer that yielded the bone3.

Pääbo suspects that other human ancestors — and new mysteries — may emerge as geneticists grind up more ancient bones for sequencing. "It is fascinating that molecular studies make a contribution in palaeontology where there is little or no morphology preserved," he says. "It is clear we stand just in the beginning of many fascinating developments."

-

References

- Krause, J. et al. Nature doi:10.1038/nature08976 (2010).

- Rasmussen, M. et al. Nature 463, 757-762 (2010). | Article | PubMed | ChemPort |

- Derevianko, A., Shunkov, M. & Volkov, P. Archaeol. Ethnol. Anthropol. Eurasia 34, 13-25 (2008).

http://www.nature.com/news/2010/100324/full/464472a.html

No Bones about It: Ancient DNA from Siberia Hints at Previously Unknown Human Relative

For the first time, researchers describe a new type of human ancestor on the basis of DNA rather than anatomy

By Kate Wong

SIBERIAN SURPRISE: DNA retrieved from a fossil found in Denisova Cave, located in the Altai Mountains, belongs to a previously unknown form of human. The excavation field camp is visible in this view from above the cave.

SIBERIAN SURPRISE: DNA retrieved from a fossil found in Denisova Cave, located in the Altai Mountains, belongs to a previously unknown form of human. The excavation field camp is visible in this view from above the cave.

For much of the past five million to seven million years over which humans have been evolving, multiple species of our forebears co-existed. But eventually the other lineages went extinct, leaving only our own, Homo sapiens, to rule Earth. Scientists long thought that by 40,000 years ago H. sapiens shared the planet with only one other human species, or hominin: the Neandertals. In recent years, however, evidence of a more happening hominin scene at that time has emerged. Indications that H. erectus might have persisted on the Indonesian island of Java until 25,000 years ago have surfaced. And then there's H. floresiensis—the mini human species commonly referred to as the hobbits—which lived on Flores, another island in the Indonesian archipelago, as recently as 17,000 years ago.

Now researchers writing in the journal Nature report that they have found a fifth kind of hominin that may have overlapped with these species. (Scientific American is part of Nature Publishing Group.) But unlike all the other known members of the human family, which investigators have described on the basis of the morphological characteristics of their bones, the new hominin has been identified solely on the basis of its DNA.

Johannes Krause and Svante Pääbo of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, and their colleagues obtained the DNA from a fossilized pinky finger bone found at Denisova Cave in the Altai Mountains of southern Siberia. The species was impossible to determine from the shape and size of the bone—it simply did not contain any diagnostic morphological traits. But there were good reasons to believe it came from a Neandertal or an early modern human. For one, the bone was recovered from a stratigraphic layer of the cave dated to between 50,000 and 30,000 years ago that contained artifacts belonging to the so-called Middle Paleolithic and Upper Paleolithic industries associated with these two groups. For another, Neandertals and modern humans were the only hominins known to have lived in this region during that time period. But the DNA the team extracted from the Denisova pinky bone turned out to be markedly different from DNA sequences previously obtained from early modern humans and Neandertals.

The researchers focused on a type of DNA known as mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA). Mitochondria are the power plants of the cell, and they have their own DNA that is separate from that housed in the cell nucleus and is passed down from mother to offspring. Because each cell has thousands of mitochondria, but only a single nucleus, mitochondrial DNA is much more abundant than nuclear DNA and is therefore more likely than the latter to be preserved in fossilized bone. To date, scientists have sequenced the mitochondrial genomes of both Neandertal and early modern human individuals, and the sequences for the two groups are quite distinctive.

Comparing the order of the genetic "letters"—or base-pairs, as they are termed—making up the Denisova mtDNA with the sequences of modern day humans and an early modern human, Krause and his collaborators found that the Denisova mtDNA differed from humans today in nearly twice as many letter positions as Neandertal mtDNAs do. Further analysis indicated that the most recent common mtDNA ancestor of the Denisova individual, Neandertals and modern humans dates to around a million years ago (making it twice as old as the most recent common mtDNA ancestor of Neandertals and moderns). This divergence date, the team says, indicates that the Denisova mtDNA is distinct from that of the H. erectus population that left Africa 1.9 million years ago, and also from that of the Neandertal ancestor H. heidelbergensis, which branched off from the lineage leading to modern humans around 466,000 years ago. As such, the researchers contend the Denisova mtDNA reveals a previously unrecognized migration out of Africa by a hitherto unknown group of hominins. (The team is holding off on giving the creature a formal name for now, but informally they refer to it as X-woman.)

"The data that they provide is certainly of the nature to arrive at the conclusions that they do," comments Stephan Schuster of The Pennsylvania State University, who worked on the recent sequencing of Archbishop Desmond Tutu's nuclear genome as well as the nuclear genome sequencing of a woolly mammoth. "All the detected sequence differences clearly indicate that this is a novel variant of a [hominin]."

Paleoanthropologist Ian Tattersall of the American Museum of Natural History in New York City noted that the finding should not necessarily come as a surprise. "We know the fossil record is far from complete, but what we have already shows that the [hominin] evolutionary bush is quite luxuriantly branching," he remarks. "One more branch is not something that ought to give us indigestion."

The association of the mystery hominin with those Middle and Upper Paleolithic artifacts is peculiar though, because elsewhere in Eurasia they have only turned up with Neandertal and modern human remains. Krause notes that it is possible that the pinky bone originated in an older, deeper layer of the cave sediments and over time got mixed in with the overlying artifacts. Thus far, however, there is no evidence for extensive perturbation. Another possibility, he says, is that the finger bone is that of an early modern human who carried an ancient mtDNA as a result of interbreeding between his or her ancestors and this previously unknown hominin group.

But other experts are not so sure about the team's interpretation of their data. "I don't know—and nobody else does—how many base-pair changes make a new species," says Erik Trinkaus of Washington University in Saint Louis, an authority on Neandertals and early modern humans. "I would like to have more than the number of mtDNA base pair differences to go on."

"The result doesn't mean that they've found a new species, and I don't believe it requires a separate pre-Neandertal migration out of Africa," argues John Hawks of the University of Wisconsin–Madison, whose research focuses on human genetic evolution. "Those explanations are both compatible with the result, but I don’t think the data require them yet." Hawks notes that the history of an mtDNA sequence—which is just a tiny fraction of a person's total DNA—does not necessarily reflect the history of a species.

A comparably distinctive nuclear genome sequence would significantly strengthen the claim that the Denisova mtDNA represents a previously unknown type of hominin. To that end, Krause and Pääbo are launching a Denisova genome project to obtain a full nuclear genome sequence from the bone that yielded the novel mtDNA. Comparisons of this genome with the full genome sequence they have obtained for the Neandertal as well as with the genomes of people living today could yield insights into the genetic changes that defined H. sapiens. "At the end we get more information about the big question [of] what makes humans humans," Krause reflects.

Meanwhile, paleoanthropologists are eager for more fossils to confirm the DNA-based claim. With luck, continued excavation at Denisova cave this summer will turn up additional remains—and put a face on this long-lost relative.

http://www.scientificamerican.com/article.cfm?id=new-hominin-species

L'homme de Denisova, nouveau cousin ?

Une troisième espèce humaine, contemporaine de l'homme de Néandertal et de l'homme moderne, aurait été identifiée par les gènes contenus dans un os de la main découvert en Sibérie.

François Savatier

Out of Africa ? Oui, l'espèce humaine a essaimé à partir de l'Afrique, mais quand ? Un fossile daté d'environ 40000 ans retrouvé en Sibérie complique l'énigme : le séquençage des gènes qu'il contenait suggère qu'il appartient à un hominidé, qui n'était ni un Néandertalien ni un homme moderne.

Le fossile provient de l'Altaï sibérien, et plus précisément de la grotte de Denisova, une grande cavité très riche en traces et artefacts préhistoriques, car elle a été occupée pendant 125 000 ans. Johannes Krause et ses collègues, de l'Institut Max-Planck de Leipzig et de diverses universités européennes et américaines, viennent de séquencer entièrement l'ADN mitochondrial contenu dans l'un des rares fossiles humains de la grotte de Denisova, un os isolé appartenant à un doigt.

L'ADN mitochondrial est issu des mitochondries, des organites cellulaires. Il contient environ 16 000 bases. Pour analyser le génome mitochondrial de la nouvelle espèce, les chercheurs ont appliqué une méthode d'amplification spécifique de séquences d'ADN (PCR modifiée), mise au point récemment pour séquencer l'ADN mitochondrial des Néandertaliens sans craindre les contaminations.

La comparaison de la séquence obtenue – la séquence complète de l'ADN mitochondrial de l'individu – a révélé qu'elle différait trop de l'ADN mitochondrial des Néandertaliens et des hommes modernes pour qu'on puisse conclure que l'individu séquencé appartenait à l'une de ces espèces. Or le fragment osseux provient d'une strate de la grotte datée entre 48 000 et 30 000 ans avant le présent… Ainsi, à une époque où des hommes modernes et des hommes de Néandertal vivaient en Sibérie, le bout de doigt de Denisova suggère fortement qu'une troisième espèce humaine y vivait aussi ! Chose remarquable, ce serait la première fois qu'une espèce humaine est découverte seulement à partir de ses gènes.

Mais de quelle espèce s'agit-il ? Les ancêtres des Néandertaliens et des hommes modernes ont divergé en Afrique, il y a environ 450 000 ans, avant que certains de leurs descendants ne quittent le continent, il y a quelque 250 000 ans pour les premiers et 100 000 ans pour les seconds. Les chercheurs ont établi un nouvel arbre phylogénétique du genre Homo intégrant la nouvelle espèce probable. L'ancêtre commun des Néandertaliens, de l'homme moderne et de l'homme de Denisova aurait vécu il y a environ un million d'années. Dans ce cas, il est impossible que l'homme de Denisova descende de Homo erectus, puisque celui-ci a migré vers l'Eurasie 900 000 ans avant que ne vive cet ancêtre commun, soit il y a 1,9 million d'années. Il semble donc qu'une vague humaine passée inaperçue jusqu'à aujourd'hui aurait quitté l'Afrique il y a un million d'années environ.

Cette découverte est plus qu'inattendue, et certains préhistoriens répugnent encore à la considérer comme certaine sur la seule base de l'ADN mitochondrial. Pour mieux apprécier la distance génétique entre la probable nouvelle espèce, Homo neanderthalensis et Homo sapiens, les chercheurs ont entrepris d'extraire de l'ADN nucléaire de l'os du doigt. Toutefois, pour vraiment convaincre les préhistoriens, il faudrait leur trouver un fossile plus complet d'homme de Denisova...

|

|

Johannes Krause/Institut Max-Planck

La grotte de Denisova est située dans un endroit sauvage de l'Altaï sibérien. Elle a été occupée par des hommes durant 125 000 ans et contient de nombreuses traces de leurs passages, dont quelques fragments de fossiles humains.

L'auteur

François Savatier est rédacteur à Pour la Science.

à voir aussi

François Savatier/Pour la Science

L'ancêtre commun aux deux espèces humaines connues et à la nouvelle espèce découverte dans la grotte de Denisova aurait vécu il y a un million d'années environ.

Pour en savoir plus

|

Sequencing the genomes of family members could lead to better treatments.Getty Images

Sequencing the genomes of family members could lead to better treatments.Getty Images

SIBERIAN SURPRISE: DNA retrieved from a fossil found in Denisova Cave, located in the Altai Mountains, belongs to a previously unknown form of human. The excavation field camp is visible in this view from above the cave.

SIBERIAN SURPRISE: DNA retrieved from a fossil found in Denisova Cave, located in the Altai Mountains, belongs to a previously unknown form of human. The excavation field camp is visible in this view from above the cave.