-

Par trichard le 9 Septembre 2013 à 15:01

Paris, 08 Août 2013

http://www2.cnrs.fr/presse/communique/3195.htm

Illustration d'un mode de nutrition par aspiration unique chez les Tétrapodes

Les recherches d'un groupe de scientifiques français, marocains et belges, publiées en juillet viennent de permettre la description d'une nouvelle tortue marine géante - Ocepechelon bouyai - découverte dans les dépôts de la fin du Crétacé des Phosphates du Maroc (Bassin des Oulad Abdoun). Elle a vécu au Maastrichien supérieur il y a 67 millions d'années.

Cette tortue fossile montre par ailleurs des adaptations uniques et poussées à la vie aquatique, illustrées par un dispositif d'alimentation par aspiration sans précédent parmi les vertébrés Tétrapodes (vertébrés munis de doigts).Téléchargez le communiqué de presse :

Références :

Nathalie BARDET Centre de recherche sur la paléobiodiversité et les paléoenvironnements (CR2P, CNRS – MNHN - UPMC, Paris), Nour-Eddine JALIL (UCAM, Marrakech), France de LAPPARENT de BROIN (CR2P, CNRS – MNHN - UPMC, Paris), Damien GERMAIN (CR2P, CNRS – MNHN - UPMC, Paris), Olivier LAMBERT (IRSNB, Bruxelles), Mbarek AMAGHZAZ (OCP, Khouribga)

Bardet N., Jalil N-E, Lapparent de Broin F., Germain D., Lambert O. & Amaghzaz M. (2013)

A Giant Chelonioid Turtle from the Late Cretaceous of Morocco with a Suction Feeding Apparatus Unique among Tetrapods. Plos One, 8(7), e63586, 1-10 + supplements. votre commentaire

votre commentaire

-

Par trichard le 9 Septembre 2013 à 14:49

Paris, 2 septembre 2013 http://www.cnrs.fr/

La grenouille de Gardiner des îles Seychelles, l'une des plus petites grenouilles au monde, est dépourvue d'oreille moyenne avec tympan mais peut cependant coasser et entendre ses congénères. Ce mystère vient d'être résolu par une équipe internationale de chercheurs menée par Renaud Boistel, de l'IPHEP1 (CNRS/Université de Poitiers). Grâce à une étude aux rayons X, elle a démontré que ces grenouilles utilisent leur cavité buccale et des tissus mous et osseux pour transmettre les sons à l'oreille interne.

Ces travaux, débutés au Centre de neuroscience Paris-Sud (CNRS/Université Paris-Sud/Université Jean-Monnet Saint-Etienne), ont été menés avec le synchrotron européen de l'ESRF à Grenoble. Les résultats sont publiés dans PNAS

du 2 septembre 2013.La perception des sons est commune à différentes lignées d'animaux et est apparue au cours du Trias (il y a 200-250 millions d'années). Bien que les systèmes d'audition des animaux à quatre pattes se soient depuis modifiés à plusieurs reprises, ils ont en commun une oreille moyenne avec tympan et osselets, qui s'est développée indépendamment dans les différentes lignées. Certains animaux, notamment la plupart des grenouilles, n'ont pas d'oreille externe comme les humains, mais seulement une oreille moyenne avec un tympan, située directement à la surface de la tête. Les ondes sonores environnantes font vibrer le tympan, et ces vibrations sont ensuite acheminées par des osselets à l'oreille interne, où des cellules ciliées les traduisent en signaux électriques qui sont envoyés vers le cerveau. Est-il possible de détecter un son dans le cerveau sans oreille moyenne ? A priori, la réponse est non, car 99,9% du son qui se propage dans l'air est réfléchi à la surface de la peau.

Cependant, pour Renaud Boistel, qui a dirigé l'équipe de chercheurs, « nous connaissons des espèces de grenouilles qui coassent et communiquent ainsi entre elles, mais sans avoir d'oreille moyenne tympanique. C'est une contradiction apparente. Les grenouilles de Gardiner ont vécu isolées dans la forêt tropicale des Seychelles depuis que ces îles se sont séparées du continent il y a 47 à 65 millions d'années. Si elles peuvent entendre, c'est que leur système d'audition est une survivance des formes de vie qui existaient du temps du supercontinent Gondwana. »

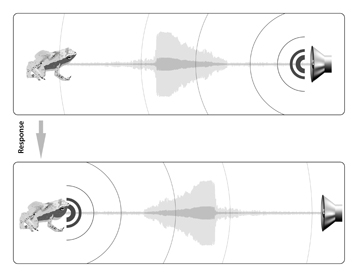

Pour prouver que ces grenouilles utilisent réellement le son pour communiquer entre elles, les scientifiques ont installé un haut-parleur dans leur habitat naturel et ont diffusé des coassements pré-enregistrés. Les mâles présents dans la forêt tropicale ont répondu, démontrant ainsi qu'ils étaient capables d'entendre les sons émis par le haut-parleur.

L'étape suivante était d'identifier le mécanisme permettant à ces grenouilles apparemment sourdes d'entendre des sons. Différents mécanismes ont été proposés : une voie de passage hors-tympan à travers les poumons, ou par des muscles reliant la ceinture pectorale à la région de l'oreille interne, ou encore par conduction osseuse. « La capacité d'un tissu biologique à transporter du son dépend de ses propriétés biomécaniques. Avec les techniques d'imagerie en rayons X que nous avons ici à l'ESRF, nous avons pu établir que ni le système pulmonaire ni les muscles de ces grenouilles ne pouvaient contribuer de façon significative à la transmission du son vers l'oreille interne, » confirme Peter Cloetens, un scientifique de l'ESRF qui a pris part à l'étude. « Comme ces animaux sont minuscules, un centimètre de long seulement, nous avions besoin d'images en rayons X des tissus mous et des parties osseuses, en résolution micrométrique, pour déterminer quelles parties du corps contribuaient à la propagation du son. »

Des simulations numériques ont aidé à explorer la troisième hypothèse, suggérant que le son était transmis par la tête elle-même. Ces simulations ont montré que la bouche agit comme un résonateur, ou amplificateur, pour les fréquences émises par cette espèce. L'imagerie synchrotron en rayons X sur différentes espèces a montré que la transmission du son de la cavité buccale à l'oreille interne était optimisée grâce à deux adaptations : réduction de l'épaisseur des tissus mous et osseux entre la bouche et l'oreille interne, et diminution du nombre de couches de tissu, toujours entre la bouche et l'oreille interne. « La combinaison de la résonance de la bouche et de la conduction osseuse permet à la grenouille de Gardiner de percevoir le son efficacement sans avoir recours à une oreille moyenne tympanique », conclut Renaud Boistel.

L'équipe internationale qui a mené cette étude comprend des chercheurs français de l'IPHEP (CNRS/Université de Poitiers), du centre de neuroscience Paris-Sud (CNRS/Université Paris-Sud/Université Jean-Monnet Saint-Etienne), de l'Institut Langevin « Ondes et Images » (ESPCI Paris Tech/CNRS/UPMC/Université Paris-Diderot), du Laboratoire de mécanique et d'acoustique de Marseille (CNRS/Aix-Marseille Université/Ecole centrale Marseille), de l'Institut de biologie systémique et synthétique (Université d'Evry-Val d'Essonne/CNRS), du Fonds de Protection de la Nature des Seychelles et de l'ESRF (synchrotron européen) à Grenoble.

© R. Boistel/CNRS

Photo d'un mâle de la grenouille de Gardiner (S. Gardineri), prise dans son habitat naturel des îles Seychelles.

© R. Boistel/CNRS

Illustration de l'expérience qui montrait que la grenouille de Gardiner peut écouter des sons. Quand le coassement de cette grenouille est diffusé par haut-parleur, les grenouilles mâles répondent

Notes :

1- Institut de paléoprimatologie, paléontologie humaine : évolution et paléoenvironnements

votre commentaire

votre commentaire

-

Par trichard le 23 Mai 2013 à 10:47

"Dodo Birds". Black and amber chalk on cream paper. By Roelandt Savery, ca. 1626. Public Domain; click for source

Any animated film starring pirates, Charles Darwin, and a dodo is going to be worthy of mention here, but Aardman Animations — of Wallace & Gromit and Chicken Run fame — has outdone itself with “The Pirates!: Band of Misfits”. I missed its theatrical run. But I happened to catch it recently and I think it’s well worth your time, especially if, like me, you enjoy witty, screwball comedies.

Here’s a taste: http://blogs.scientificamerican.com/artful-amoeba/2013/05/22/pirates-charles-darwin-and-one-very-un-extinct-dodo/

As soon as I saw her, it was obvious the pirates’ “parrot” Polly was a dodo. Which was a bit unexpected, considering the film also features Charles Darwin and Queen Victoria. By that time, dodos had been dead as … well, dodos for well over 100 years. This goes on to become a major plot point in the film.

Dodos were giant flightless pigeons endemic to the Indian Ocean island of Mauritius, east of the coast of Madagascar. The species went extinct sometime in the late 1600s, barely 100 years after their discovery by Portuguese sailors. Although hungry Dutch traders and other seamen have historically been blamed for the loss by eating the naive birds, feral introduced animals like pigs may have been the larger force. Regardless, the world is poorer for it. At least for two hours, I got to pretend there was at least one left, which was fun. One quibble: actual dodos reached about 3 feet high and weighed at least 20 pounds — possibly as much as 40. The bird in the film seems to be adorably chicken-sized.

This movie was based on the first book a series called “The Pirates! In An Adventure with Scientists”. That was also the film’s title in the United Kingdom. Strangely, the subtitle was changed to “Band of Misfits” in America, Australia, and New Zealand. Hypotheses abound on the reason, including US audiences’ presumed distaste for science and certain Americans’ known distaste for Charles Darwin.

Certainly, it’s not the first time a UK title has been changed to make it more palatable or “understandable” to Americans (“Sorcerer’s” Stone, anyone?). And don’t get me started on the shamefulness of replacing Sir David Attenborough’s timeless narration and script with a dumbed-down Oprah version, as was done to the US version of “Life“. Still, considering they didn’t change the content, if a new subtitle got more American backsides into “Pirates” movie theater seats, I can’t object too much.

votre commentaire

votre commentaire

-

Par trichard le 23 Mai 2013 à 10:42

An analysis of chemicals in primate teeth shows that a Neandertal infant nursed exclusively for a little more than 7 months

By measuring the relative amounts of barium and calcium on a tooth's growth lines, scientists showed that a Neandertal infant probably switched to a solid diet relatively early. Image: Ian Harrowell, Christine Austin, and Manish AroraThe changing ratios of calcium and barium in the teeth of modern humans and macaques chronicle the transition from mother’s milk to solid food — and may provide clues about the weaning habits of Neandertals, a new study suggests.

The predominant mineral in the tooth enamel of primates is hydroxyapatite, a form of calcium phosphate. But trace elements present in the bloodstream that are chemically similar to calcium, such as strontium and barium, can be incorporated into enamel as it calcifies, says Manish Arora, an environmental chemist at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York. Teeth begin forming in the gums before birth, and they record daily growth lines throughout their development, so they are good archives of diet and chemical exposure — even in infants.

Previous research has shown that variations in the strontium-to-calcium ratio preserved in teeth provide insight into infant diet, including the age at which children were weaned.

In the new study, Arora and his colleagues looked at barium-to-calcium ratios in the teeth of macaques and humans with known diet and breastfeeding habits, including 'baby teeth' shed by children who had been part of a broader medical study.

The results showed that little if any barium was transferred to either humans or macaques before birth, says Arora. But the proportion of barium recorded in tooth enamel shot up immediately after birth, because breast milk contains high levels of the element. Ratios waned as mothers began to supplement the infants’ diet with other food, and then dropped to low levels when breastfeeding ceased, the researchers report in Nature.

Dental demographics

But the study's most intriguing data may be those gleaned from the tooth of a Neandertal infant. The results suggest that the infant was exclusively breastfed for a little over 7 months, and then the mother’s milk was supplemented with other food for another 7 months. After that, barium levels dropped rapidly, suggesting a sudden end to breastfeeding.Arora says that 14 months is relatively early to wean a child: humans in non-industrial societies stop breastfeeding at an average age of about 2.5 years.

The team's results were based on a single sample of Neandertal tooth, which makes it difficult to draw broad conclusions. Perhaps Neandertals typically weaned their young more quickly than humans, suggesting that they may have had children at shorter intervals, says Louise Humphrey, an anthropologist at the Natural History Museum in London. But she says it is also possible that the abrupt end to breastfeeding indicates that the infant’s mother may have fallen ill or died.

Both scenarios have profound implications for Neandertal social structure, says Humphrey. A mother with a large brood would probably have required help with child care — suggesting that Neandertal families and group members routinely assisted each other. And if weaning occurred because the mother was ill or absent, individuals such as siblings or other adult relatives might have stepped in to help raise the orphan, since a previous study suggested that the infant lived to age 8. “Regardless, we have to accept that there were other adults caring for this individual,” says Humphrey.

Weaning age affects many aspects of human demographics, including the minimum time between a woman’s pregnancies, says Holly Smith, a palaeoanthropologist at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. That, in turn, affects the overall rate of population growth. Analysis of teeth found at archaeological sites, therefore, could help researchers infer demographic information about ancient populations.

votre commentaire

votre commentaire

-

Par trichard le 18 Avril 2013 à 11:45

- 18 April 2013

- Magazine issue 2913. Subscribe and save

- For similar stories, visit the Editorials and Human Evolution Topic Guides

WHEN 9-year-old Matthew Berger stumbled upon an odd-looking bone in 2008, he could not have anticipated the import of his discovery. But his father Lee, a palaeontologist, had an inkling.

The shoulder and jawbone embedded in the rock turned out to come from a 2-million-year-old member of the human family, with anatomical features that suggest it is one of our early ancestors. Since then, more remains of Australopithecus sediba have been discovered, and the latest work on them is enriching our understanding of human evolution (see "Signs of human skin found on ancient ape ancestor").

We have unearthed more and more ancient human species in recent years. Rather than there being a neat evolutionary line from ape-like ancestor to modern human, we now think there was a lot of interbreeding. A. sediba is just one such ancestor; others may await discovery.

The focus of fieldwork is also shifting. The most famous discoveries come from East Africa, but A. sediba was found in the Malapa cave, north-west of Johannesburg. So southern Africa may be the place to seek insights into our origins. It will take sharp young eyes to spot them.

votre commentaire

votre commentaire Suivre le flux RSS des articles de cette rubrique

Suivre le flux RSS des articles de cette rubrique Suivre le flux RSS des commentaires de cette rubrique

Suivre le flux RSS des commentaires de cette rubrique

Mon petit cahier de sciences naturelles