Sockeye salmon have been in decline for the past 20 years in the Fraser River.Stuart Westmorland/CORBIS

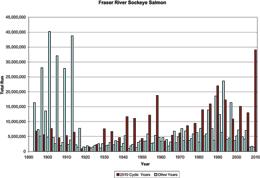

Sockeye salmon have been in decline for the past 20 years in the Fraser River.Stuart Westmorland/CORBISIt's the biggest run of sockeye salmon in British Columbia since 1913. Some 34 million fish are thronging the Fraser River as they return from the sea to spawn, federal regulators announced on 31 August. The event, following two decades of decline in salmon-run numbers, is taking fisheries scientists by surprise — and causing frustration across the fishing industry, which is largely unable to access the windfall.

One reason is that fisheries have been slow to open, unable to balance environmental and economic demands in the face of sheer fish numbers. And with about 80% of the salmon concentrated in one lake system, the Shuswap, the riches are poorly distributed. Because fishing quotas tend to be allocated geographically, a fisherman in a different part of the river system might be unable to benefit from the influx.

The cost of all this could be high — a loss of between 5 million and 10 million fish in potential catch, according to Carl Walters at the University of British Columbia Fisheries Centre in Vancouver.

This year's unexpected boom has led to even more intense speculation about the state of the sockeye population. The 2009 salmon run reportedly saw only around 1.5 million fish returning to the river. The Canadian government's Cohen Commission, established in 2009, is now looking at the current state of the sockeye population and potential causes of the decline. The commission aims to make recommendations for the future sustainability of salmon stocks by mid-2011.

Given the existence of models that predict fluctuations in salmon populations, why has this year's glut come as such a shock? Fisheries and Oceans Canada, the government agency in Ottawa, Ontario, that runs the models and regulates the salmon fishing industry, has been criticized for failing to predict it.

Sue Grant, fisheries biologist at Fisheries and Oceans Canada, explains that the models are full of uncertainties: "They are based on biological information from historical and real-time catches to estimate the abundance," she says. "The forecasts are probability distributions based in part on extrapolation from historical data sets."

In any case, long-term predictions will not help fishermen this year. The first commercial fishery on the stocks opened on 8 August, but many others remain closed. And with a fishing fleet in tatters after years of decline, a fast response to this kind of sudden bounty was always going to be difficult.

Management issues

At almost 1,400 kilometres in length, the Fraser River supports around 40 separate populations of sockeye salmon and has been managed for the past 100 years. The complex fisheries management system is in place to ensure a balance between stock sustainability and economic viability — thus supporting both the First Nations fisheries and the commercial industry.

During the late run season in August and September, the Pacific Salmon Commission in Vancouver carries out daily assessments to determine salmon abundance. These focus on biological data sets, ranging from genetic analyses of stock composition to measurement of fish size and numbers using hydro-acoustic monitoring.

The salmon's life cycle takes it on a four-year journey from spawning in the river to the Gulf of Alaska, and back. Whereas salmon migratory routes in the river system are closely monitored, the two years they spend in the Gulf remain a black box. "The early marine stage is very important for setting total marine survival, but nobody really knows what environmental indicators could affect the salmon," says Nathan Mantua, a fisheries scientist at the University of Washington in Seattle.

And this year the marine survival rate, normally 8%, was 25%. "This in itself is not unprecedented, but it has happened in a naturally big yield year in the life cycle," says Walter.

"There's research going into understanding this, but it's a natural cycle that has been like this since before industrial times and fisheries management," says Mike Lapointe, chief biologist at the Pacific Salmon Commission. So a serendipitous mix of factors could have led to the bumper run.

Room for improvement

But better population models are clearly needed. What could be done to improve them?

"We have a history of developing models in the past and applying these in the forecast mode," explains Mantua. "But they fail because the models are not capturing what's important."

More monitoring of the ocean environment, including the food web, may help to clarify the survival rates of the salmon. But, says Lapointe, what really matters is how many salmon spawn. "The sockeye lay between 3000–4000 eggs. Small variations in spawning success from year to year can have a huge difference in the numbers and consequent survival out in the oceans," he says.

These biological complexities are made even more challenging by the way the fisheries are managed, but Fisheries and Oceans Canada defend the systems they use. "We spend six months setting up this framework and when people complain in season, we don't want to break down all the rules negotiated over months, based on a single interest," says Sue Farlinger, the agency's director-general for the Pacific region.

And there is an extra layer of complexity, she explains: "What's changed in the past 15–20 years is that the fishery now protects weaker stocks as well as setting quotas for stronger stocks. If weak and strong stocks are co-migrating like this year, we have to be very careful with the quotas."

http://www.nature.com/news/2010/100903/full/news.2010.449.html

Questions à Thuy Le Toan, responsable du groupe « Biomass » du Centre d’études spatiales de la biosphère de Toulouse.

Questions à Thuy Le Toan, responsable du groupe « Biomass » du Centre d’études spatiales de la biosphère de Toulouse.